Today is Medical Communications Day, a day to celebrate and highlight our profession and what it entails. Every day we identify health needs, seek to understand data, relay key messages to wider audiences and raise heath awareness in the community. Ultimately, we thrive off of knowing we are doing our bit to make a better informed and healthier world.

With recent Black Lives Matter protests across the world highlighting the inequality, discrimination and racism the black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) community continue to face, I have found myself reflecting deeply on not only what the protests stand for as a whole, but also on how much more is to be done to understand the health inequalities that BAME people face, and how we can play our part as health communicators to promote positive change.

With recent Black Lives Matter protests across the world highlighting the inequality, discrimination and racism the black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) community continue to face, I have found myself reflecting deeply on not only what the protests stand for as a whole, but also on how much more is to be done to understand the health inequalities that BAME people face, and how we can play our part as health communicators to promote positive change.

COVID-19 has laid bare the stark health inequalities that exist in our society. Yes, we have all spent the last three months worried and anxious about catching COVID-19 and the impact that this may have on the health of ourselves and those closest to us. We’ve all cautiously navigated our trolleys round people in the supermarket aisle, waved thank you to the postman through the window for dropping our deliveries on the doorstep, and done awkward greetings with strangers on the pavement to make sure everyone has enough room to pass by. And yet while we all were concerned about catching COVID-19, recent governmental data has showed that both the infection and mortality rate of COVID-19 is much higher in the BAME population than the white population.

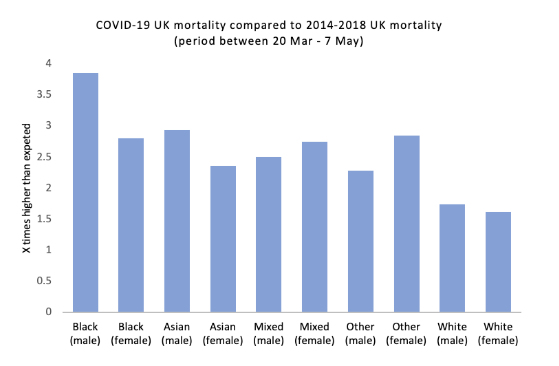

Black men are 4.2x more likely to die from COVID-19 than white men – Public Health England, COVID-19 disparities

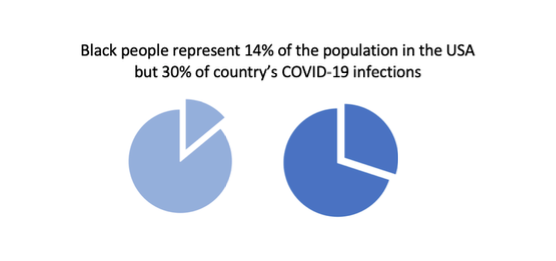

Approximately 13% of the UK’s population are BAME, and yet the BAME population has made up 36% of those who have been admitted into critical care with COVID-19 and 16.2% of all COVID-19 deaths. This is not unique to the UK; similar patterns in health inequality have been seen in other countries with high numbers of COVID-19 cases, including the US and Brazil. For an infectious disease that we have repeatedly been told does not discriminate, how can there be such racial variations in health outcomes?

The percentage of people with co-morbidities linked to serious cases of COVID-19 (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension) is proportionally greater amongst BAME people than the white population, which may be a contributing factor to the disparity in these statistics.

The percentage of people with co-morbidities linked to serious cases of COVID-19 (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension) is proportionally greater amongst BAME people than the white population, which may be a contributing factor to the disparity in these statistics.

The recent UK government report ‘Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19’ states that after all the risk factors for COVID-19 are taken into account, such as age, sex, obesity and comorbidities, there is no difference in intensive care hospital admittance or mortality rate between BAME and white people. But is that enough to explain why there is such a difference in health outcomes? If studies show underlying risk factors such as obesity and cardiovascular disease – not someone’s race – reduce their health outcomes from COVID-19, does that mean racial inequalities have not played a part?

Health is not simply the end-state reached once all biologically predetermined factors have been accounted for. To fully understand health, and health inequalities, we must also acknowledge the multitude of other societal factors that impact one’s health, such as education, poverty, and access to healthcare.

The coronavirus might not discriminate, but societies do – Hardeep Mathuru

For example, a BAME person may not be at increased risk of COVID-19 because of their race directly, but instead, because of the racial inequalities they experience in society. Take poverty for instance. Statistically, BAME people are twice as likely to live in poverty than white people. This is driven by many of the social inequalities experienced by BAME people, including: restrictions caused by migration status, higher rates of unemployment, and lower levels of educational attainment. Within the government’s disparity report it notes that there is a higher rate of COVID-19 infection and mortality among those who live in deprived regions compared to those in wealthier regions. This demonstrates that by not addressing the many interconnected societal inequalities the BAME population face, we will not be adequately addressing health inequalities either.

The difference in health outcomes between BAME and white people extends far beyond COVID-19 and the UK:

- Black people are 4x more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act than white people in the UK.

- Double the percentage of Latinx people (of any race) in the USA are not covered by health insurance compared to white people.

- The maternal mortality rate for non-white women is 3.5x higher than white women in Brazil.

With recent COVID-19 statistics highlighting the racial inequalities that exist in the UK, the government has expressed that there is much more to be done to tackle this issue and has established the NHS Race and Health Observatory in its response. This Observatory will be a new research centre that aims to analyse and address the health inequalities in the BAME community in the UK to make policy recommendations to the government.

But on an individual level, as those who work every day to create a healthier world, what should we be doing to make a difference and play our part?

- Educate ourselves, on the racial inequalities that exist in society, including how these inequalities create disparity in health.

- Support others, including the many organisations and individuals out there who are committed to reducing racial inequalities in society. We can all support these organisations through our time, donations and willingness to learn.

- Lobby for change, by demanding and supporting the policies that can be put in place which address racial inequalities on a national and international level.

While there is no doubt COVID-19 has made all of us worry about our livelihoods, our families and ourselves, the disease has laid bare the disparity in health outcomes BAME people face, and very well may be the catalyst for positive change.